OTC

The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 [1] required that drugs be labeled with adequate directions for safe use, mandated pre-market approval of all new drugs, such that a manufacturer would have to prove to FDA that a drug was safe before it could be sold, and prohibited false therapeutic claims for drugs. Public outcry over the Elixir Sulfanilamide incident led to the passage of this Act. The solvent in this untested product was a highly toxic chemical analogue of antifreeze; over 100 people died, many of whom were children.

Enforcement of the new law came swiftly. Within two months of the passage of the act, the FDA began to identify drugs such as the sulfas that simply could not be labeled for safe use directly by the patient–they would require a prescription from a physician. The ensuing debate by the FDA, industry, and health practitioners over what constituted a prescription and an over-the-counter drug was resolved in the Durham-Humphrey Amendment of 1951. The bill requires any drug that is habit-forming or potentially harmful to be dispensed under the supervision of a health practitioner as a prescription drug and must carry the statement, “Caution: Federal law prohibits dispensing without prescription. [2]

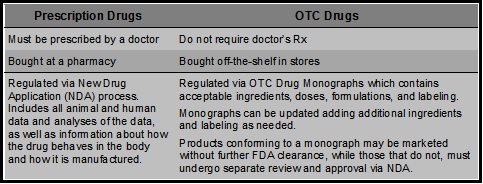

What are over-the-counter (OTC) drugs and how are they approved? [3] [6]

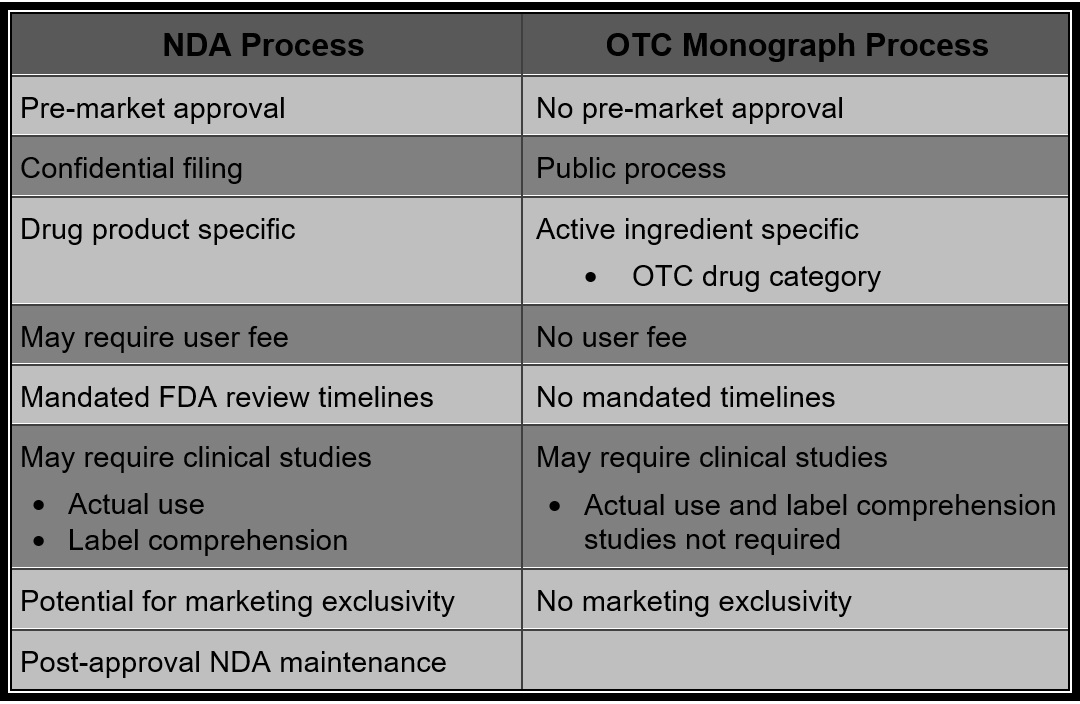

OTC drugs are drugs that have been found to be safe and appropriate for use without the supervision of a health care professional such as a physician, and they can be purchased by consumers without a prescription. These drugs are sometimes approved under applications like new prescription drugs, but more often they are legally marketed without an application by following a regulation called an OTC drug monograph.

An OTC drug monograph tells what kind of ingredients may be used to treat certain diseases or conditions without a prescription, and the appropriate dose and instructions for use. OTC products that meet a monograph’s requirements may be marketed without FDA review. OTC products that do not fit under an existing monograph must be approved under an application like the applications for prescription products.

Over-the-Counter (OTC) Drug Monograph Process [4]

The Over-the-Counter (OTC) Drug Review was established to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of OTC drug products marketed in the United States before May 11, 1972. It is a three-phase public rulemaking process (each phase requiring a Federal Register publication) resulting in the establishment of drug monographs for an OTC therapeutic drug class.

The first phase was accomplished by advisory review panels. The panels were charged with reviewing the active ingredients in OTC drug products to determine whether these ingredients could be generally recognized as safe and effective for use in self-treatment. They were also charged with reviewing claims and recommending appropriate labeling, including therapeutic indications, dosage instructions, and warnings about side effects and preventing misuse.

The panel’s conclusions would be published in the Federal Register in the form of an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPR). A period of time was allotted for interested parties to submit comments or data in response to the ANPR.

According to the terms of the review, the panels classified ingredients in three categories as follows:

- Category I: generally recognized as safe and effective for the claimed therapeutic indication

- Category II: not generally recognized as safe and effective or unacceptable indications

- Category III: insufficient data available to permit final classification

The second phase is the FDA’s review of active ingredients in each class of drugs, based on the panel’s review of ingredients, public comment, and new data that may have become available. FDA’s conclusions would be published as a tentative final monograph (TFM) in the Federal Register. Another period of time is allotted for interested parties to submit comments or data in response to the TFM.

The third and last phase of the review process is the publication of the final rule in the form of a drug monograph. After publication, a final monograph may be amended, either on the Commissioner’s own initiative or upon the petition of any interested person. OTC drug monographs are continually updated to add, change, or remove ingredients, labeling, or other pertinent information, as needed.

The OTC drug monographs establish conditions under which certain OTC drug products are generally recognized as safe and effective GRAS and GRAE). These monographs define the safety, effectiveness, and labeling of all marketing OTC active ingredients. Once a final monograph is implemented, companies can make and market an OTC product without the need for FDA pre-approval. Products containing active ingredients or indications that are non-monograph require an approved New Drug Application (NDA) for marketing.

OTC Drugs Developed Under the OTC Drug Monograph Process [5]

The Division of Nonprescription Regulation Development (DNRD) in the Office of Drug Evaluation IV is responsible for the development of the OTC drug monographs. Data presented to support the safety and efficacy of different active ingredients in a particular drug monograph are reviewed by appropriate scientific personnel. Efficacy data may require the input of a medical officer and/or statistician from a prescription review division. Carcinogenicity or other animal toxicology data may require input from a CDER pharmacologist. So, while DNRD is considered to be the lead division in the development of an OTC drug monograph, reviewers from multiple divisions within the Office of New Drugs (OND) are involved in this process.

Although pre-approval by FDA for drugs marketed under a drug monograph is not required, many companies seek assurance that the product they intend to market under the drug monograph complies with the regulations. These cases are primarily handled by DNRD unless consultation with Compliance or another review division is necessary. If a drug cannot comply with the drug monograph, an IND and approved NDA is necessary before the drug product may be marketed.

[1] http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/Origin/ucm054826.htm

[2] http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/History/ThisWeek/ucm117875.htm

[3] http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/Transparency/Basics/ucm194951.htm

[4] http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ucm317137.htm

[5] http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ucm209647.htm

General Information for OTC Drugs:

Rx Drugs Now Available Without a Prescription

In February 1996, the Food and Drug Administration approved the “switch” of Nicorette gum to over-the-counter (OTC) status. In the summer of 1996, the FDA also approved the prescription-to-OTC switch of two transdermal nicotine patch products (Nicotrol in July 1996 and NicoDerm CQ in August 1996). Switches of other nicotine patch products followed (Prostep in December 1998 and Habitrol in November 1999). In October 2002, the FDA approved Commit, the first lozenge dosage form containing nicotine.

The patch, gum, and lozenge join more than 700 other OTC drugs that would have required a prescription only 20 years ago, because the FDA, in cooperation with panels of outside experts, determined they could be used safely and effectively without a doctor’s supervision.

The FDA has given OTC approval to drugs such as Children’s Advil and Children’s Motrin (ibuprofen), Orudis KT and Actron (ketoprofen), and Aleve (naproxen sodium) for pain relief and fever reduction; Femstat 3 (butoconazole nitrate) for vaginal yeast infection; Pepcid AC (famotidine), Tagamet HB (cimetidine), Zantac 75 (ranitidine hydrochloride), Axid AR (nizatidine), and Prilosec OTC (omeprazole magnesium) for heartburn; Rogaine (minoxidil) for hair growth; and Claritin (loratadine), the first non-sedating antihistamine.

The Switch Process

The original Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 made no clear-cut distinction between prescription and OTC drugs. The 1951 Durham-Humphrey amendments to the act set up specific standards for classification.

The amendment requires that drugs that cannot be used safely without professional supervision be dispensed only by prescription. Such drugs may be deemed unsafe for nonprescription use because they are habit-forming or toxic, have too great a potential for harmful effects, or are for medical conditions that can’t be readily self-diagnosed.

All other drugs can be sold OTC. A drug must be made available without a prescription if, by following the labeling, consumers can use it safely and effectively without professional guidance.

The process of reclassifying drugs from prescription to OTC status is referred to as an “Rx to OTC switch.” Drugs are commonly switched one of two ways: under the “OTC drug review,” or by a manufacturer’s submission of additional information to the original new drug application.

The OTC drug review, which began in 1972, is an ongoing assessment of the safety and effectiveness of all nonprescription drugs. In the first phase of the OTC drug review, panels of nongovernment experts review active ingredients in marketed OTC drug products to determine whether they can be classified as safe and effective. The panels also review prescription ingredients to determine whether some are appropriate for OTC marketing. About 40 former prescription-only drug ingredients have been switched by this process.

The second common path to OTC approval is under the new drug application process. Under this process, manufacturers submit data to the FDA showing the drug is appropriate for self-administration. Data are submitted in a new drug application or a supplement to an already approved drug application. Often the submission includes studies showing that the product’s labeling can be read, understood, and followed by the consumer without the guidance of a health care provider. The FDA reviews the new data, along with any information known about the drug from its prescription use. Under the new drug application process, some drugs are approved initially as OTC drugs, but most are first approved for prescription use and later switched to OTC.

In almost every case for the first drug switched in a drug category, the agency has sought the recommendation of a joint advisory committee made up of members of the agency’s Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee and another advisory committee with expertise in the type of drug being considered. For example, because Rogaine is for conditions of the hair and scalp, representatives of the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee participated.

Benefit-Risk Comparison

When considering an Rx-to-OTC switch, the key question for the FDA is whether consumers can self-select a drug for a certain use, and achieve the desired medical result without endangering their safety. Will consumers be able to understand and follow label directions, diagnose the condition themselves–or at least recognize the symptoms they want to treat–and whether routine medical examinations or laboratory tests are required for continued safe use of a drug. No easy risk-benefit formula exists. The FDA does a case-by-case review of each drug because each drug raises unique issues.

Concerns about side effects can sometimes be managed by approving OTC drugs at lower doses than their prescription counterparts. The drugs must still be effective for the short-term symptoms for which they’re intended.

Labeling

Labeling is an influential element in the OTC risk-benefit comparison. Labeling can alert consumers to potential problems. Labeling of all drugs must be clear and truthful. For OTC drugs, the intended uses, directions, and warnings have to be written so consumers, including individuals with low reading comprehension, can understand them. Labeling should also provide information when professional guidance may be necessary.

In March 1999, the FDA finalized regulations to increase the readability of OTC labels by making the language more consumer-friendly and standardizing the format, including where important information is placed.

http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm143547.htm